Things that don’t exist in Spain

If you’ve never been to Spain and believe everything you read online (especially in Camino groups) you might end up filling your backpack to the brim. Why? Because apparently, according to some of those posts, Spain doesn’t have anything.

But is that really true? Can you not find ice, peanut butter, electrolytes or even flip flops in Spain?

It’s normal to have lots of questions before traveling to a new country, especially if it’s your first time.

I remember my own first trip to the UK when I was about 15 or 16. I went with a school group and stayed with host families. Some of the questions we got from them were… interesting.

Things like: “Do you have washing machines in Spain?”

And years later, when I moved to Ireland, I heard more of the same. A Spanish friend mentioned her dad was an engineer, and people were genuinely surprised: “Wait, there are engineers in Spain?”

This was from people who had actually been to Spain, and seen our roads, airports, infrastructure…

So, yes, some stereotypes are hard to shake.

And when I scroll through Camino forums, I see similar assumptions.

People ask if they need water purification tablets. Or vaccines. Fortunately, these are not the most frequently asked questions, but they come up every now and them.

In case there are any doubts, let me clear that up right now: No, you don’t need water purification tablets to walk the Camino in Spain. You don’t need any vaccines to get into the country either.

So, over the last few months, I’ve been compiling a list of the questions I see most often in forums and groups. Some are understandable, others a bit surprising. But what truly baffles me are some of the answers.

Take decaf coffee, for example.

Someone asked if it was available in Spain.

A few people quickly replied there’s no decaf in Spain.

One person even said they had just walked the Camino and hadn’t found decaf anywhere. I was curious, so I asked what they had asked for. Their answer was “decaf”, in English.

Well, that explains it.

Of course they couldn’t find it. No one understood what they were asking for. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist!

Someone else asked if it was acceptable to take leftovers home from a restaurant.

The response?

“No, that’s not something people do in Spain. They won’t understand if you ask for a doggy bag.”

Well, if you say “doggy bag” in English in a Spanish restaurant, no, they probably won’t understand.

And if you try Google Translate and ask for “una bolsa para el perro”, they might hand you a bag of scraps for your pet—as they did with another poor pilgrim!

But does that mean you can’t take your leftovers home?

Not at all. It’s actually perfectly normal to do so in Spain. But you need to ask in proper Spanish.

(Get this episodes’s transcript for free here)

So, I compiled a list and ended up with 25+ items that people often worry they won’t be able to find in Spain.

Then, I went to supermarkets, pharmacies, sports stores… and even those catch-all chinos (discount stores run by Chinese families). All the typical places you’d go shopping in Spain. Just to confirm that everything on my list could be easily found.

And guess what?

I found everything. I had to search a bit harder for one of the items… but I found that one eventually, just not in the first shop I checked.

Here’s the thing: sometimes it’s not about what’s available, but how you ask for it and where you’re looking.

For example, in the UK or Ireland, you can often buy over the counter medicine like painkillers or cold remedies at a supermarket.

But in Spain? Nope. You won’t find those in the supermarket.

That doesn’t mean they’re not available. You just need to go to a pharmacy.

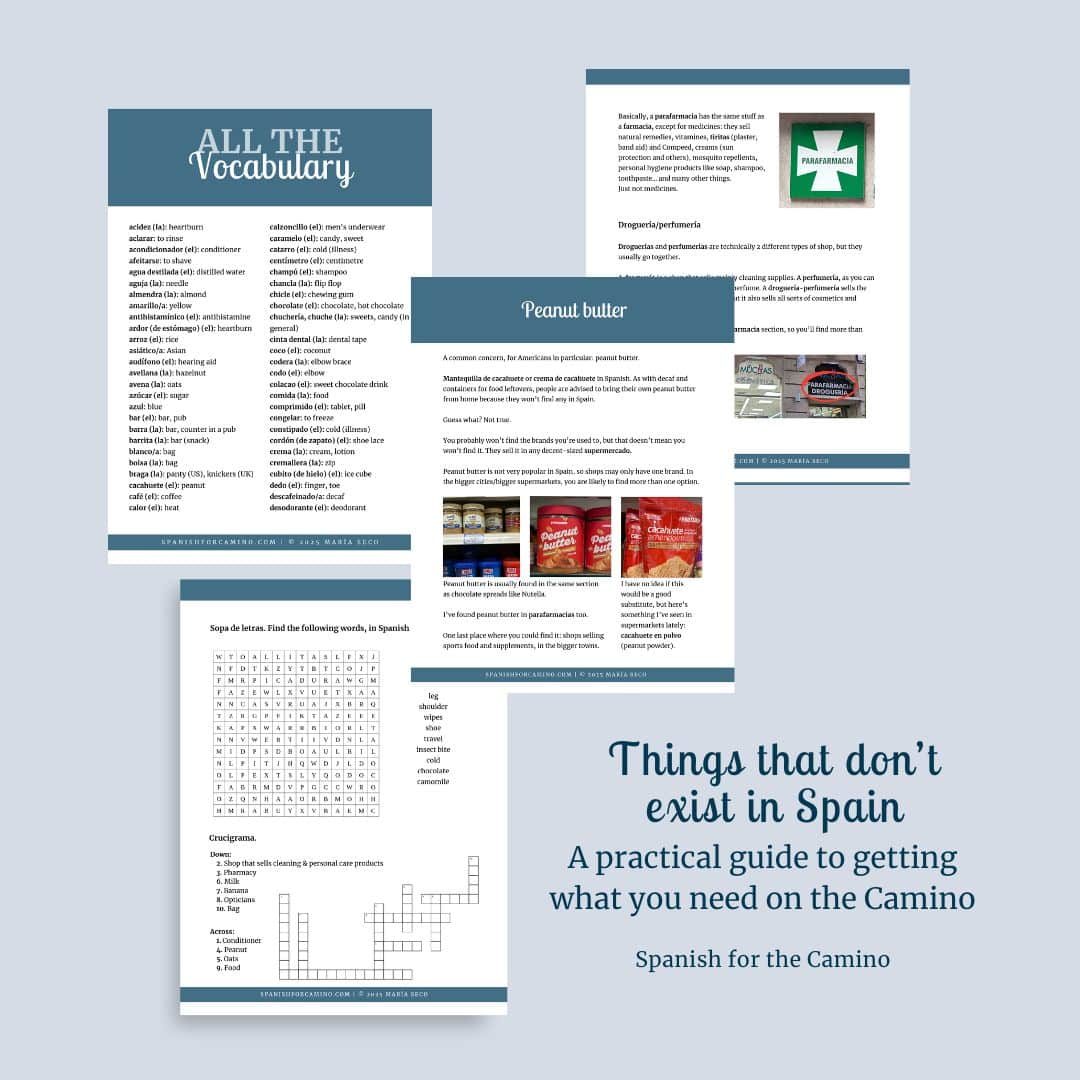

I’ve turned all this info into a super practical guide called: “Things That Don’t Exist in Spain”

(Spoiler: They do exist).

Inside, you’ll find:

-

A list of 25+ commonly asked items

-

Where to find them

-

What to say in Spanish so people understand you

-

Cultural tips, like how to find a pharmacy open 24/7—even on Sundays and holidays

-

Photos to prove it all!

Want more?

Make sure you don’t miss any posts or announcements by subscribing for free here. You’ll receive the transcripts + vocabulary guides + interactive exercises of episodes 1-5 of the Spanish for the Camino podcast. And… you’ll get access to exclusive content too.